Welcome to the AES Blog

Australia’s Indigenous Evaluation Strategy: Making good on the promise of centring Indigenous experience

by Danielle Campbell, Marlkirdi Rose Napaljarri and Linda Kelly

Indigenous people in Australia and internationally are increasingly calling for monitoring and evaluation that supports self-determination, decolonisation and better outcomes for their communities.

In this blog, we share some of what we have learned together – as Indigenous and non-Indigenous community development advocates and evaluators – from our work in the Tanami Desert in Central Australia. We hope that by sharing some of our key lessons, from 10 years of trials, successes and failures, we can contribute to the discussion about whether and how genuinely co-created Indigenous evaluation can be done in Australia.

Recent developments in Indigenous evaluation approaches

Decolonising evaluation means using methods and approaches that support self-determination and ensuring that Indigenous people, with their unique worldviews and values, are involved in monitoring and evaluation governance.

As well as the call for decolonisation of evaluation, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers have called for improved monitoring and evaluation of Indigenous services and programs through increased resourcing, more attention to demonstrating outcomes and impacts valued by Indigenous people, culturally appropriate data collection, analysis and feedback methods, and the active engagement and training of Indigenous evaluators.

In October 2020, the Australian Government took a major step towards improving the quality of Indigenous program evaluation by releasing the first national Indigenous Evaluation Strategy. The Strategy embraces the overarching principle that Indigenous people, perspectives, priorities and knowledges need to be front and centre in evaluations that concern them. It includes an accompanying Guide with useful information on how to do this.

Not far enough

However, having worked for more than 10 years with the Central Land Council (CLC) to support them to monitor and evaluate their Community Development Program, we think the Strategy does not go far enough in recognising monitoring and evaluation (M&E) as a challenging, non-linear, time-consuming and deeply political process that needs careful navigation. The Guide includes only one reference to checking whether Indigenous people can participate in evaluations on an equal footing and makes no reference to evaluation politics.

In contrast, the Indigenous evaluation literature increasingly points to engaging with worldviews and power differences to co-create Indigenous evaluations that acknowledge merit through multiple perspectives (see here and here).

Our experience is that this can be a challenging process. To work effectively in this area, evaluators have to have more than technical expertise. They must exercise humility, respect, and transparency, and give up control over the evaluation project, plus walk the fine line of collecting evidence that aligns with Indigenous ways of knowing while meeting the varied purposes of government funders (see here).

Insights from our work with the Warlpiri Education and Training Trust

The Institute for Human Security and Social Change (IHSSC) – where we now all work – has collaborated with the Central Land Council (CLC) to establish an M&E approach for the Warlpiri Education and Training Trust (WETT).

WETT was established in 2005, as a project under the CLC’s Community Development Program. Warlpiri trustees have so far invested over $30 million of gold mining royalties in education and training programs that benefit four remote Warlpiri communities in the Tanami Desert, plus extensive community engagement and governance processes.

WETT M&E has been facilitated by the CLC, with support from Institute evaluators, since 2009, informed by the belief of staff that it would support improved process, outcomes and accountability to Indigenous people and help demonstrate that supporting Indigenous locally-led development is more effective than centralised, top-down programming.

Over the last decade the CLC, WETT and IHSSC have experimented with many different evaluative approaches and methods in trying to assess WETT process and outcomes. Three things we’ve learnt stand out.

Lesson One – Different worldviews = different priorities, outcomes and metrics

Because Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders operate from fundamentally different worldviews, they don’t necessarily value the same outcomes. Non-Indigenous stakeholders are often focused on education, training, employment and Indigenous capacity development outcomes. Warlpiri aspirations include these objectives, but they are underpinned by others that are generally more important to Yapa (Warlpiri people), including maintenance of culture, language and connection to country, respectful relationships and self-determination. This creates an inherent tension in terms of what constitutes success and which metrics can and should be used to measure it (and whether measurable comparable metrics are helpful). A challenge also highlighted by others in the AES interested in Indigenous evaluation (here).

Lesson Two – Non-Indigenous evidence preferences can easily dominate

Views on the purpose of M&E, the type of information that constitutes quality evidence and the best methods to generate it will differ. Both Warlpiri (Yapa) and non-Indigenous (Kardiya) people involved agreed that accountability to Yapa is the primary intention of M&E for WETT, but CLC staff have also focused on a secondary accountability to the Australian Government given their oversight of royalties.

This resulted in the addition of standard design, monitoring and evaluation methods and processes to the core community development process. The CLC contracted organisations to design WETT projects (based on Warlpiri priorities), managing this through detailed funding agreements – that specified activities, outcomes, indicators and sometimes detailed log-frames – and regularly analysing project reports and expenditure. The project data produced has been helpful in providing accountability to Government. Although results are limited, enough of the ‘right’ numbers have been produced to show that some Warlpiri kids are engaging in early learning, while others are engaging in primary and finishing secondary school, and some adults are completing certificate training and getting jobs. Combined with financial reporting on the $32 million WETT has spent to date, this has been key in convincing Government that WETT is an effective way of administering royalty payments for education and training projects.

The CLC, however, was concerned that the project data may not be rigorous or ‘objective’ enough to convince external stakeholders that the program was also making progress towards more substantial program outcomes (increased governance capacity and increased education and training outcomes for Warlpiri people) and impact (Warlpiri people living strong lives on country). Other approaches to produce the ‘objective’ data that would win over such audiences were explored, generally with limited success despite significant time and resource investments.

Trial A – Trial of a participatory community capacity assessment measurement tool

The WETT committee agreed to trial a participatory community capacity measurement tool developed in the Pacific and used successfully in Indigenous Australian communities in Queensland (see here).They enjoyed the first full day workshop where they rated themselves against nine pre-determined domains of community capacity and developed action strategies to address capacity gaps over the next six months. However, when the committee reconvened with CLC staff six months later to review progress on ‘their’ action strategies and reassess their capacity in each domain, none of the actions had been progressed and members saw no value in repeating the measurement of themselves through the tool.

Trial B – Developing an economic evaluation methodology

The CLC explored an economic evaluation of the CD Program, including the WETT project. Health economists with experience in Indigenous program evaluation were engaged to develop a social return on investment methodology. They identified data availability and access at the remote Aboriginal community level, as well as the diversity of projects being funded under the CD Program, as major challenges in setting up this kind of evaluation. There was a suggestion for Aboriginal decision-making groups to fund at least some consistent community-level interventions in different locations to generate comparable evidence, but the CLC considered this inconsistent with the program objective of promoting Indigenous decision-making and control. The economic evaluation was not progressed.

These well-intentioned attempts by CLC staff (including co-author Danielle) to do what they considered to be robust M&E took the process away from Warlpiri and their focus on mutual accountability between WETT decision-makers, landowners, communities, project partners and the CLC, using metrics that were not very meaningful to them.

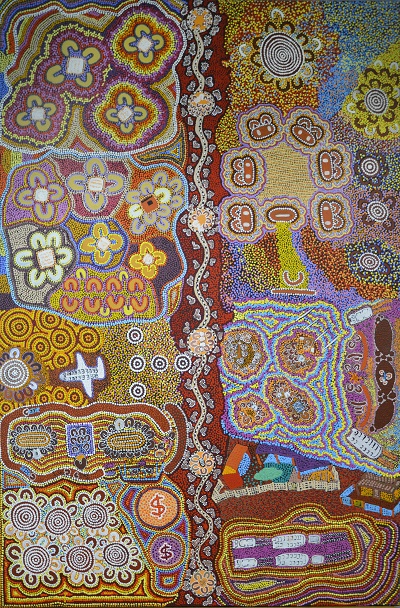

WETT decision-makers have engaged with some of the data produced by formal monitoring systems (to varying degrees depending on their numeracy and literacy), but like other Yapa they are generally more interested in a two-way flow of information. Yapa have expressed a preference for methods that support relationality and the co-creation of WETT knowledge through sharing stories, interviews and collaborative paintings.

We have our own Yapa ways of watching closely to assess how things are going, giving encouragement and feedback so things can improve, and sharing information through stories and paintings. But Kardiya don’t see this or maybe they don’t understand it.” (Marlkirdi Napaljarri)

Lesson Three – Power differences mean you can’t just mix evaluation priorities and processes

You can’t simply ‘mix’ evaluation processes that work well for Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders. This ignores power dynamics that can skew evaluation and privilege certain ways of assessing programs. The original focus on Government and non-Indigenous priorities, using forms of evidence valued by Government and non-Indigenous people was a pragmatic approach – and accountability to Warlpiri was happening in other ways – but given limited resources, it was at the expense of working to set up a genuinely co-created evaluation approach designed to meet everyone's needs.

While the CLC has always engaged Aboriginal people in deciding which approaches to stick with and which ones to shelve, monitoring and evaluation was being approached largely as a technical process, which required a technical solution, rather than something to be co-created with Warlpiri like the rest of the WETT work.

A new opportunity

A new 18-month WETT funded project is providing an opportunity to bring the WETT, CLC, partners and the Institute together to co-create an evaluation framework that will now try to weave together different priorities and knowledge systems. The Ground Up Monitoring and Evaluation Approach being developed in Northern Australia and the Indigenous Canadian concept of “two-eyed seeing” – bringing together the strengths of Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing – are informing this approach. They highlight the need for robust evaluation approaches for programs operating in ‘shared jurisdictions’ that equally privilege Indigenous and Western knowledges and methods, in order to produce results and recommendations that are viewed as credible and relevant by all involved. This is requiring us to pay very close attention to differences in power and perspectives, including that of the Institute’s non-Indigenous staff, to deliberately build a shared approach.

This is slow and complex work. It draws on long-term relationships grown through advocating for WETT in meetings from Lajamanu to Canberra and working together on the ground in the Tanami Desert. It involves experienced Warlpiri researchers and WETT champions with a deep understanding of the local context and Yapa ways of assessing value, and non-Indigenous researchers with knowledge of the strengths and limitations of different evaluative forms, who are committed to valuing Indigenous knowledge and shifting power.

Valuing and navigating different knowledge systems is not something that can be workshopped, written into an evaluation plan and delivered. In our experience, it’s facilitated by a shared commitment to ‘two-eyed seeing’, trusting relationships that allow for frank cross-cultural conversations, and endless learning and adaptation.

We are still in the talking, trialling and refining phase and yet to see if and how co-created evaluation works in this context.

The Indigenous Evaluation Strategy is right to call for centring Indigenous people in evaluation, but it presents it as a largely technical and apolitical process. It would benefit from more examples of the challenging reality of bringing together different knowledge systems and more detail on what it takes to support good Indigenous evaluation in practice. Currently it runs the risk of increasing the focus on evaluation of Indigenous programs, but failing to support the generation of information and evidence that will lead to change.

We acknowledge the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the lands in which we conduct our business. We pay our respects to ancestors and Elders, past and present. We are committed to honouring Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ unique cultural and spiritual relationships to the land, waters and seas and their rich contribution to society.