Welcome to the AES Blog

Evaluating programs in new normal times: Lessons from Constable Care, Western Australia

by Kwadwo Adusei-Asante

COVID-19 has changed our way of life, including how we evaluate programs. The pandemic has rendered conventional evaluation approaches difficult to execute, and programs have faced new delivery challenges. These are challenging times for organisations that are required to deliver programs and measure agreed outcomes for their funders.

This blog draws on my experience with Constable Care Child Safety Foundation in WA. During these uncertain times, we have been forced to think outside the box and adopt new ways of doing evaluation. Our focus has been on capturing evaluation data when ‘what works’ is preferred over ‘the ideal’.

About Constable Care

Constable Care provides child safety education. The organisation works to empower young people aged 4-18 years to find creative harm prevention solutions to issues that affect them including bullying, mental health, peer pressure, personal safety, cybersafety, gambling, and drug and alcohol abuse.

Constable Care delivers eight programs through which it engages over 100,000 children and young people every year and reaches over 500,000 families in WA. The programs range from 40 minutes theatrical performances to ten weeks shows, as well as an excursion destination for primary school children to learn pedestrian, bicycle and public transport travel safety skills.

Constable Care needs to demonstrate outcomes to funders and key stakeholders. I have been providing evaluation advice and support to Constable Care over the last two years. As a result, Constable Care has digitised its evaluation procedures and developed an evaluation framework that captures baseline and program data using a range of quantitative/qualitative-based evaluation techniques. While each program is different and are evaluated with tailored models, largely, the models capture students’ demography, perceptions, knowledge, behavioural intentions, and overall satisfaction with the program.

Evaluations at Constable Care in COVID-19

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Constable Care delivered most of its programs through face-to-face contacts in classrooms and in the community. This meant that most of its evaluation data could be collected at such events using iPads. While children were still attending school, the pandemic lockdown meant it was no longer possible for program staff or evaluators to visit schools.

Following consultations with its funders and stakeholders, Constable Care developed online versions of its programs and uploaded them on its website and social media platforms. Under this arrangement, Constable Care has relied on teachers to use its online video shows to educate students on harm prevention.

The new normal required innovation and adaptation of Constable Care evaluation procedure. Initial discussions about developing web-based surveys and embedding them in the online videos’ description tabs was discarded due to technical difficulties and concerns with data validity. After much deliberation, we adopted a proxy evaluation technique augmented with google analytics.

At the height of the pandemic, we used a proxy technique to collect evaluation data to measure the impact of the new online video content. Teachers became proxies who collected Constable Care’s evaluation data before and after the children watched the online videos. The teachers received evaluation forms and instruction documents, which explained the purpose of the evaluation activity and how the data should be collected.

Little is known about the use of proxies in program evaluation. It is not a perfect technique, as it presents ethical issues pertaining to potential conflict of interest and data quality, and heavily relies on the cooperation of proxies. Practitioners may want to explore the technique as an option if physical contact with evaluation respondents is practically impossible and in settings where trust is low, or the evaluator is a stranger. In our case, the cooperation of teachers has been commendable, enabling the organisation to obtain rich and useful evaluation data.

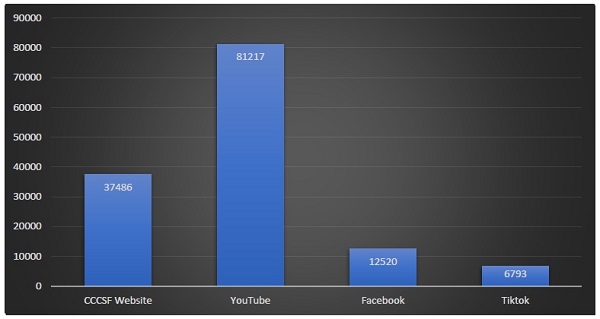

Additionally, we are using google analytics to capture quantitative data on Constable Care’s online videos. Google analytics is an online analytics service offered by Google which tracks and reports website traffic. Google analytics has enabled Constable Care to capture ‘number of views’ data on each of the four platforms listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Number of views of Constable care online videos 15 March 2020 and 04 July 2020

Figure 2 suggests that while the organisation’s online video content primarily targets WA students, the videos have been viewed by people from four continents. This unintended outcome has been welcomed by the funders of Constable Care and presents an opportunity to work internationally.

Figure 2: Constable Care online video analytics: Facebook

COVID-19 has presented many challenges to professionals in various fields, program evaluators not excepted. On the brighter side, COVID-19, has prompted new ways of working and being. In my view, innovative thinking may not necessarily require inventing new models or theories, but an exploration of ideas and tools we would normally take for granted. In uncertain times, the quest for perfection may need to be set aside to focus on what is feasible.

Currently, WA is easing restrictions—normalcy is gradually being restored. This notwithstanding, Constable Care’s proxy evaluation technique has enabled the organisation to evaluate its programs in full and partial COVID-19 lockdown modes. Rather than simply being a compromise, the pandemic has enabled Constable Care to discover new possibilities and build new relationships, while collecting robust data to show it. Evaluation practitioners need to focus on finding the right evaluation solutions that are contextually feasible.

--------------------------

Dr. Kwadwo Adusei-Asante is a Senior Lecturer at Edith Cowan University in Western Australia.

We acknowledge the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the lands in which we conduct our business. We pay our respects to ancestors and Elders, past and present. We are committed to honouring Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ unique cultural and spiritual relationships to the land, waters and seas and their rich contribution to society.